April 12, 2015

What Science-Fiction is About

The Hugo Award is one of the longest-running and most prestigious awards in Science-Fiction. As some readers may by now be aware there is a major controversy regarding this year's award process: a right-wing group organized a campaign against 'social justice' inspired nominees and was mostly successful in getting their own slate nominated. Some people have called for "No Award" votes in all categories.

It's always hard to say what (or whom) an award like this is supposed to be for, and that's part of what the so-called 'Sad Puppies' group says this controversy is about. However, given the group's close ties to 'GamerGate', their inclusion of members with extreme views on race and gender, their association with extremely offensive personal attacks and even threats of violence, along with some of their own comments, it doesn't seem like this is what it's about at all. It seems more likely that what they are upset about is the ways in which the award has recognized attempts to paint sympathetic portraits of non-privileged viewpoints.

Despite the title of this post, I don't plan to make any grand generalizations about 'what science-fiction is about,' nor do I plan to say anything about what the Hugo Awards should be for. What I do want to say (and show) is that one thing (among many) that science-fiction has been about for many decades is the sympathetic portrayal of non-privileged viewpoints. I think this is something it should continue to be about. Similar points have been made at great length and in great detail by Matthew David Surridge, who refused a nomination for Best Fan Writer award after learning that he was on the Sad Puppies slate. But I feel the need to add some more specific historical examples, to show that the following tirade by Brad Torgersen, one of the leading Sad Puppies organizers, is nonsense on stilts:

A few decades ago, if you saw a lovely spaceship on a book cover, with a gorgeous planet in the background, you could be pretty sure you were going to get a rousing space adventure featuring starships and distant, amazing worlds. If you saw a barbarian swinging an axe? You were going to get a rousing fantasy epic with broad-chested heroes who slay monsters, and run off with beautiful women. Battle-armored interstellar jump troops shooting up alien invaders? Yup. A gritty military SF war story, where the humans defeat the odds and save the Earth. And so on, and so forth.These days, you can't be sure.

The book has a spaceship on the cover, but is it really going to be a story about space exploration and pioneering derring-do? Or is the story merely about racial prejudice and exploitation, with interplanetary or interstellar trappings?

There's a sword-swinger on the cover, but is it really about knights battling dragons? Or are the dragons suddenly the good guys, and the sword-swingers are the oppressive colonizers of Dragon Land?

A planet, framed by a galactic backdrop. Could it be an actual bona fide space opera? Heroes and princesses and laser blasters? No, wait. It's about sexism and the oppression of women.

Finally, a book with a painting of a person wearing a mechanized suit of armor! Holding a rifle! War story ahoy! Nope, wait. It's actually about gay and transgender issues.

Or it could be about the evils of capitalism and the despotism of the wealthy.

Later, Torgersen contrasts the 'good' science-fiction, characterized by the motto "To Boldly Go Where No One Has Gone Before!", which he says came from the '60s, '70s, and '80s, with the 'bad' science-fiction "proffered in the 2000s and beyond" which is all "about racism, sexism, or gender issues, or sex".

As Surridge points out in the above-linked post, it's quite ironic that Torgersen not only uses a motto from Star Trek - he uses the gender-inclusive version introduced in The Next Generation! Star Trek - especially the later series - is an extremely optimistic vision of the future. What's so optimistic about it? Well, aside from the total equality of races - even non-human ones! - and genders, we have all of these people flying around space and whenever they encounter something new the first questions they ask are does it have rights? and are those rights being respected? Of course this optimistic vision is marred by various inconsistencies, especially in The Original Series, and the command staffs of the starships the various series center around tend to be dominated by white male humans. But, at least from The Next Generation foreword, we are presented with a picture of the broader Starfleet that is much more diverse than this, including, for instance, Picard taking orders from female admirals.

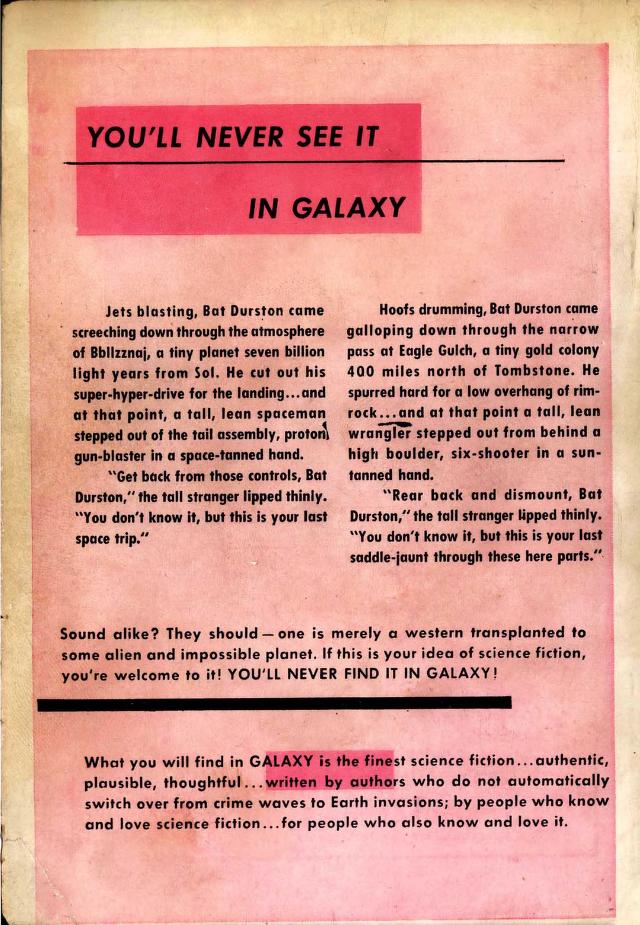

Leaving Star Trek aside, here's the back cover of the first issue of Galaxy Science Fiction, dated October, 1950:

Galaxy was a major force in shaping science-fiction during the entire period Torgersen indicates, and Galaxy advertised itself consistently as science-fiction for grown-ups. Part of what that meant was dealing with serious themes and not just writing juvenile adventure stories.

This raises the question, what unique resources does science-fiction have for dealing with serious themes? If one is going to write serious literature, why not write realistic fiction?

One of the things science-fiction frequently asks us to do is to imagine worlds radically different from our own. One of the ways this device can be used is to ask us to imagine a world in which the currently privileged viewpoint is not privileged. This, of course, will typically involve sympathetic representation of non-privileged viewpoints, and this is something science-fiction writers have been trying to do for a very long time. A lot of these attempts have involved issues about race, gender, and sexuality, and a lot of these attempts have won Hugos, and a lot of these Hugos were awarded in the '60s, '70s, and '80s, when (according to Torgersen) science-fiction was boldly going where no one had gone before.

Here are some examples of Hugo winners and nominees from that period:

- Venus Plus X by Theodore Sturgeon won Best Novel in 1961. It involves a world in which everyone is a hermaphrodite. After a sexual encounter, both participants conceive.

- Stranger in a Strange Land by Robert Heinlein won Best Novel in 1962. As is well known, this is a hippy, free-love novel.

- "Riders of the Purple Wage" by Philip Jose Farmer won the Hugo for Best Novella (shared with Anne McCaffrey's "Weyr Search") in 1968, the first year it was awarded. This story describes a society in which bisexuality is the norm and incest is not stigmatized.

- "Aye, and Gomorrah" by Samuel Delany was nominated for Best Short Story in 1968. The story deals with 'spacers', who are neuter, being fetishized by 'normal' earth humans and used as prostitutes.

- "The Sharing of Flesh" by Poul Anderson won Best Novelette in 1969. In this story, an expedition finds a human culture in a stranded colony where, in order to be accepted into manhood, a boy must kill a man and ritually eat his genitals. A member of the expedition is killed for this purpose. The story centers around his widow, who must balance her desire for vengeance with the need for a sympathetic understanding of the culture. A theme here, which one also sees in many other works of science-fiction is that there may be more to 'primitive' and 'barbaric' customs than meets the eye.

- "Winter's King", one of Ursula Le Guin's Gethen stories, won Best Short Story in 1970. The inhabitants of Gethen live most of their lives as hermaphrodites. During their adult lives, they 'kemmer' on a 28 day cycle. During the period of kemmer, they take on one sex or the other (not always the same one) in order to mate. This is clearly being used by Le Guin as a device for exploring the ways in which viewing people under gender categories shapes our social interactions.

- The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula Le Guin won Best Novel in 1970. This is also about Gethen, and involves a 'normal' human traveler who struggles to fit in and figure out how to relate to people who don't fit gender categories.

- "When It Changed" by Joanna Russ was nominated for Best Short Story in 1973. Explorers discover a lost colony in which all the men have died and the colony has survived by artificial reproduction. Marriage is practiced among the (all female) colonists, and married couples parent children together. The explorers who discover it are all male. The story centers around a mother who fears (unnecessarily, as it turns out) that her daughter may fall in love with one of the men rather than marrying a woman as 'normal' people do.

- Another Le Guin story, "The Day Before the Revolution," was nominated for Best Short Story in 1975. This story is about an aging female political leader who struggles to adjust to the world created by the social revolution she engineered.

- Asimov's "The Bicentennnial Man" won Best Novelette in 1977. This is a story about justice in a far more explicit way than most of the others: it's about a robot who wants 'human rights'.

- "Houston, Houston, Do You Read?" by Alice Sheldon (aka James Tiptree, Jr.) won Best Novella in 1977 (shared with Spider Robinson's "By Any Other Name"). In this story, a group of astronauts are accidentally transported to the future where, they discover, there are no men. After studying them, the future astronauts who pick them up determine that their psychological problems, especially their propensity for violence, are too great to be dealt with and they will have to be euthanized.

- "The Persistence of Vision" by John Varley won Best Novella in 1979. This story involves a commune of deaf-mutes who develop a language based solely on touch. Sex is part of the language and is participated in freely, even by children.

- "Buffalo Gals, Won't You Come Out Tonight" by Ursula Le Guin won the Hugo for Best Novelette in 1988. The story is about a child who survives a plane crash in central Oregon and finds herself in the world of Native American folklore.

Now, I'm not saying that all of these stories are (or intend to be) super-progressive. I'm certainly not saying they're all 'politically correct'. Political correctness means, at least, trying to avoid giving offense. Many of these stories are doing just the opposite - trying on purpose to offend! But what they are all doing, in one way or another, is trying to make us look at things from a perspective different from the one that is actually privileged in our society. In many of these cases, this has to do with gender and sexuality; in a few it has to do with race. And, of course, this kind of stuff can be traced back further than 1960 - indeed further than the genesis of the Hugo Awards - in science-fiction. I'd be remiss if I didn't mention Sturgeon's "The World Well Lost," a story specifically about homosexuality which appeared in 1953, before they began giving Hugos for short stories.

I'm also not saying that all of these stories succeeded in sympathetically portraying alternative perspectives. As long as the writers were mostly straight white men (though note that the list about includes a lot of works by women), that was a hard thing to do. It is very difficult - some would say impossible - to enter into a non-privileged viewpoint when one occupies a position of privilege. But this is something science-fiction can help us do, when it's done well, and that is certainly a thing worth doing.

Posted by Kenny at April 12, 2015 11:07 PM| Trackbacks |

TrackBack URL for this entry: http://blog.kennypearce.net/admin/mt-tb.cgi/764

|

Comments

Though Martin is unhappy with the situation, he is not one of the people who recommends voting "no award" in all categories.

Posted by: Protagoras at April 13, 2015 7:50 AMYou're right - my mistake. The Independent has Martin in the headline, but it's Philip Sandifer who is quoted recommending the 'no award' response. I'm updating the post accordingly.

Posted by: Kenny Pearce at April 13, 2015 8:14 AM